Unlucky

I spoke with a new leader at a church last week who expressed her frustration that she never caught a lucky break, that every victory she had won had been so hard fought, and how it hadn’t felt like that at the last place she worked.

We’ve all found ourselves in those seasons – where we’re not phenomenally unlucky, but we just don’t catch the breaks we could. Things that could work out easily if we were 5% luckier just don’t. Those cumulative inconveniences – getting an “I’ll think about it” when you wanted a “yes,” getting an “I guess I can cover one shift” when you hoped they’d agree to chair the event – can be exhausting. Why can’t it be just a little bit easier?

It turns out there’s a possibility that it can be, and we can make ourselves just a bit luckier by holding fast to those things we know we should be doing anyway. In an article by Brian Lui, he outlined the concept of “upside decay.”

“Upside Decay”

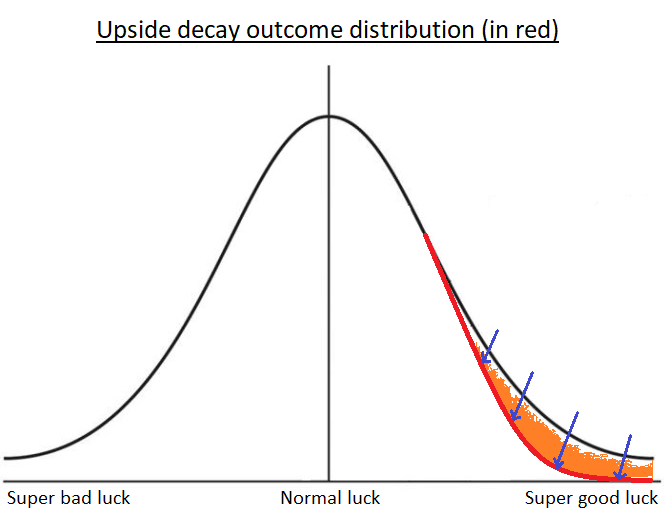

We can imagine all possible outcomes for one event, from the incredibly unlucky to the incredibly lucky, as distributed along a bell curve. Our frustrating streaks of not catching a break can be represented as a slight collapsing in of the “lucky” side of the curve. Even if this change is marginal, it can have huge impacts because lucky breaks were already uncommon.

In the hypothetical equation he lays out, if, to get lucky, we need to get 6 consecutive positive outcomes that all have a 50% chance of success, our cumulative chance of success is 1.56%. That’s about a 1 in 65 chance. Meaning if this is something you keep at every day, you’ll get your lucky break around once every 2 months on average – that’s not bad!

However, if that proportion of success drops to 30% every time you try, then the probability of getting 6 yeses becomes 0.07% or 1 in 1,429. That would mean you would get that same lucky break on average about once every four years. Ouch.

“Upside Decay” in Churches

Here’s what that might look like in a church example, inspired by my conversation the other day.

You want to launch a new program for kids in your neighborhood. You need to get the head of your children’s council on board (50% chance), and after they’re on board, you bring it to the rest of the council for a vote (50% chance). If they approve it, you need to see if facilities staff are willing or available to set the building up for the additional event (50%). Once you get a sign-off from facilities, you have to bring it to the leadership council to get the additional funding approved (50%). Once they approve it, you take information about the program to the local school to talk to their administrators about promoting the program to families that attend there (50%). Only then do you have to hope the time and day you picked actually works for the neighborhood families as well as you think it will (50%).

Obviously, this is massively oversimplified, and we all know that some of those percentages are well over 50% (and some are well under), but you get how a lucky break is really a series of the marginal odds happening to break in your favor.

So why is it that in some contexts, we can wrangle that 1 in 65 success rate, and in some, it’s more like 1 in 1,429?

Causes of Decay

Lui says the “upside decay” (the shift towards 1 in 1,400) happens when our “weak ties” no longer perceive us as virtuous and therefore are marginally less willing to want to help us out. Say we’ve burned some bridges in our context – maybe we were a bit snarkier with some of the facility staff than we should have been, or we blew off the school admin when she wanted the church to help fund the back-to-school party. When we need those loose ties to agree to something, and it’s a bit of a toss-up, they don’t have a solid reason to help or not help; they are now marginally less likely to help you.

And that margin, that drop from a 50% chance to a 30% chance, is all it takes for that program to all of a sudden take not months but years to get off the ground.

The leader I talked to hadn’t burned any bridges; she was just new. As I thought about her and upside decay, I found myself in a frustrating position as a person who helps launch innovative ideas as part of their career. I had to tell her that she might need to back-burner for a few months and spend some time building the social capital that could get her from 30% to 50%. She needed to build a reputation of what Lui calls “virtue” – that we’re good people who people might want to help, that we’re on others’ teams.

That we’re Christlike. That we’re loving, kind, generous, and humble. Turns out, the secret sauce to lucky breaks is made of the fruit of the spirit.

So what do we do?

How to be Luckier

Well, that’s the easy one. We know this one.

We are kind.

We are compassionate.

We are true to our word.

We love those around us well.

We remember that we are Christ-followers first and everything else second.

And trust that some lucky breaks are coming.

0 Comments